Introduction in Valeur, H. (2014) India: the Urban Transition – a Case Study of Development Urbanism. Copenhagen, The Architectural Publisher, pp. 27-40.

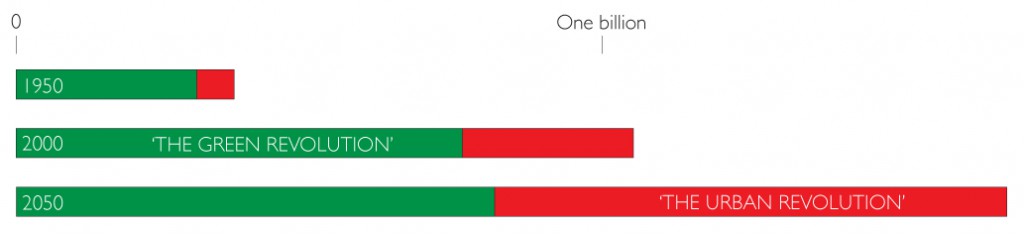

During the second half of the twentieth century, India experienced a “green revolution”, which enabled the population to almost triple – from 372 million in 1950 to 1,054 million in 2000. Most of this growth however, took place in rural areas. Thus, at the turn of the century only about a quarter of the total population lived in urban areas.

During the coming half century, however, India is expected to undergo an “urban revolution” in which more than 90 percent of the total population growth will take place in urban areas. With the urban population expected to triple – from 292 million in 2000 to 875 million in 2050 – India will see more urban growth than any other country during this period, at the end of which more than half of its population is expected to be living in urban areas.1

This transition – from a primarily rural to a primarily urban society – is going to have profound and widespread implications for the individual human being and for humanity at large.

The integration of more than half a billion more urban dwellers over a fifty-year period poses a huge challenge for a country where resources and capacities are already often stretched to the limit but it also offers huge opportunities, inasmuch as it may provide people with a way out of poverty, oppression and ignorance.

More than half a billion people in search of opportunities and prosperity in cities, adopting new urban lifestyles and related patterns of consumption, could stimulate economic growth globally. But it could also result in widespread and long-lasting environmental devastation and resource depletion while possibly pushing climate change beyond a fatal tipping point, thus adversely affecting human life everywhere and for generations to come.

However, it could also lead to insights and inventions that may improve future human life everywhere.

How India’s cities develop is thus important to all of us, although it is, of course, of the greatest importance to the people of India.

Will the urban transition of India help create opportunities and prosperity for the many? Or are overpopulation and uncontrolled urbanization going to become dragging influences on development? Will the living conditions of the urban population be improved through access to new technologies, more educational opportunities and better health care? Or will the urban “ills”, such as pollution, stress, social isolation and physical inactivity, destroy urban life?

In short, will the urban transition of India be successful, as it has been in many other places, or will it prove to be a failure, on a scale that we have never experienced before?

The green revolution

Since its independence in 1947, India has been spared of major famines (in contrast to a number of other Asian countries2) and life expectancy has more than doubled.3

This amazing achievement can largely be attributed to increased agricultural production, especially following the introduction of the Green Revolution in the late 1960s.4 High-yield crops, modern farming technologies and industrial farming methods, including the extensive use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers, however, not only served to make farming more productive but also led to the overexploitation and pollution of both soil and water.

Thus, farmers have to invest in more expensive equipment to dig ever deeper for water and have to invest in more and more pesticides and fertilizers to keep up productivity. This puts many farmers in a hopeless economic situation and may even have been the trigger of a wave of suicides among Indian farmers.5

The urban revolution

Despite the often desperate situation, in many rural areas of India, urban migration remains comparatively low (compared to China, for instance6) indicating that urban life in India does not offer much better prospects than rural life.

In fact, most of the people who try to flee rural misery end up in urban slums, where living conditions are usually not much better than what they were fleeing from and where they don’t have much hope of ever being able to significantly improve their situation.

Making cities more inclusive and improving urban welfare, in addition to making cities resilient and urban life sustainable, are critical challenges when it come to making a success of the urban revolution of countries such as India.

The culture

Indian culture is often associated with its rural traditions. As Mahatma Gandhi put it:

“We are inheritors of a rural civilization. The vastness of our country, the vastness of the population, the situation and the climate of the country has, in my opinion, destined it for a rural civilization.”7

This is, however, not the only truth. In fact, India is the inheritor of one of the greatest ancient urban civilizations: the Indus civilization. And Indian culture has developed in constant dialogue with – being influenced by and itself influencing – other great cultures.8

However, at the time Mahatma Gandhi made his remark (in 1929), the vast majority (nearly 90 percent) of the Indian population did, in fact, live in rural areas. Today, the majority (more than 2/3) of the population still lives in rural regions but, as previously mentioned, this is expected to change within the next generation.

In this process of transition, Indian culture may become transformed beyond recognition.

The Indus Civilization

It could be said that Indian culture has been formed by village life – Mahatma Gandhi said: “India lives in her seven and a half lakhs villages”9 – and by invading cultures (especially the Moghuls and the British). It has its roots, however, in one of the most sophisticated and technologically most advanced ancient civilizations – perhaps the most. At its height, more than four thousand years ago, the Indus Civilization consisted of a network of settlements around – and extending far beyond – the Indus River.

The infrastructures of water in these settlements are said to have been “far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than those [found] in many areas of Pakistan and India today.”10

These settlements included possibly more than a thousand villages, towns and cities that were scattered over a huge land area (about a quarter of India’s total land area today) with each of the largest of the cities covering more than 100 hectares.11

In the cities, there were large public facilities, such as the Great Bath in Mohenjodaro, dockyards and granaries, but unlike other ancient civilizations, there don’t seem to have been any monumental structures for kings or priests, indicating that the Indus Civilization might not have been based on strong central control but rather on decentralized decision-making. Furthermore, a surprisingly few number of weapons have been found and as for the supposed “fortifications” it is still unclear whether they were, in fact, constructed for military purposes and not rather to prevent flooding. Despite the apparent lack of a strong, militarily or religiously-based central power, the Indus Civilization seems to have been characterized by prolonged political stability.

Moreover, the fact that most houses were relatively similar, built of standard bricks (measuring 7 x 14 x 28 cm) with a central courtyard and private amenities, such as baths and toilets connected to wells or reservoirs and public sewerage and drainage systems, suggests that the Indus Civilization may also have been a relatively egalitarian civilization.

The social

Today, India is home to about one third of the world’s poorest people12 and to a few of the world’s richest people.13

The recent appointment of Indian born-and-raised Satya Nadella as the new CEO of Microsoft testifies to India’s role as a leading player in the global IT industry, at a moment in time when many Indian children are still deprived of the possibility of education altogether or are receiving only extremely minimal education.14

And while India recently launched a mission to Mars that – if successful – would make this country a member of a rather exclusive club,15 the majority of the Indian population still don’t have access to a toilet.

Thus, India is, in a way, like an endless desert of misery and backwardness dotted with tiny oases of wealth and progress. And these “oases” are not even whole cities but are merely gated compounds and communities within cities – the rest of the cities being an admixture of people struggling to reach middle class status or simply to make it through the day.

This is indeed a country rife with contrasts, contradictions and potential conflicts,16 a country that is faced with the overriding challenge of getting its resources, which are actually abundant,17 and its inventiveness, which is outstanding in so many ways, to spread out – or to “trickle down”, as it were – to the vast majority of its population.

The environment

Apart from the social challenges, India faces grave environmental challenges. These include the pollution of basic human needs such as air, water and food; depletion of groundwater, woods and many other natural resources; increased waste production, land degradation and greenhouse gas emissions; loss of ecosystems and biodiversity.

In 2014, India is ranked 155th out of 178 countries in the Environmental Performance Index18 and is ranked 174th in terms of air pollution alone.

The cost of environmental degradation has been estimated at more than five percent of the GDP, with more than half of these costs being caused by air pollution (indoor and outdoor); one-third of these costs being caused by the degradation of farmland and forest; and the rest of the costs being caused by inadequate water supply and sanitation.19

This may not only put severe constraints on development but may also be “impossible or prohibitively expensive to clean up later”.20

Different paths of development

It would appear that China has been much more successful than India in lifting people out of poverty – and maybe even in fighting pollution and other ills. Why is this so?

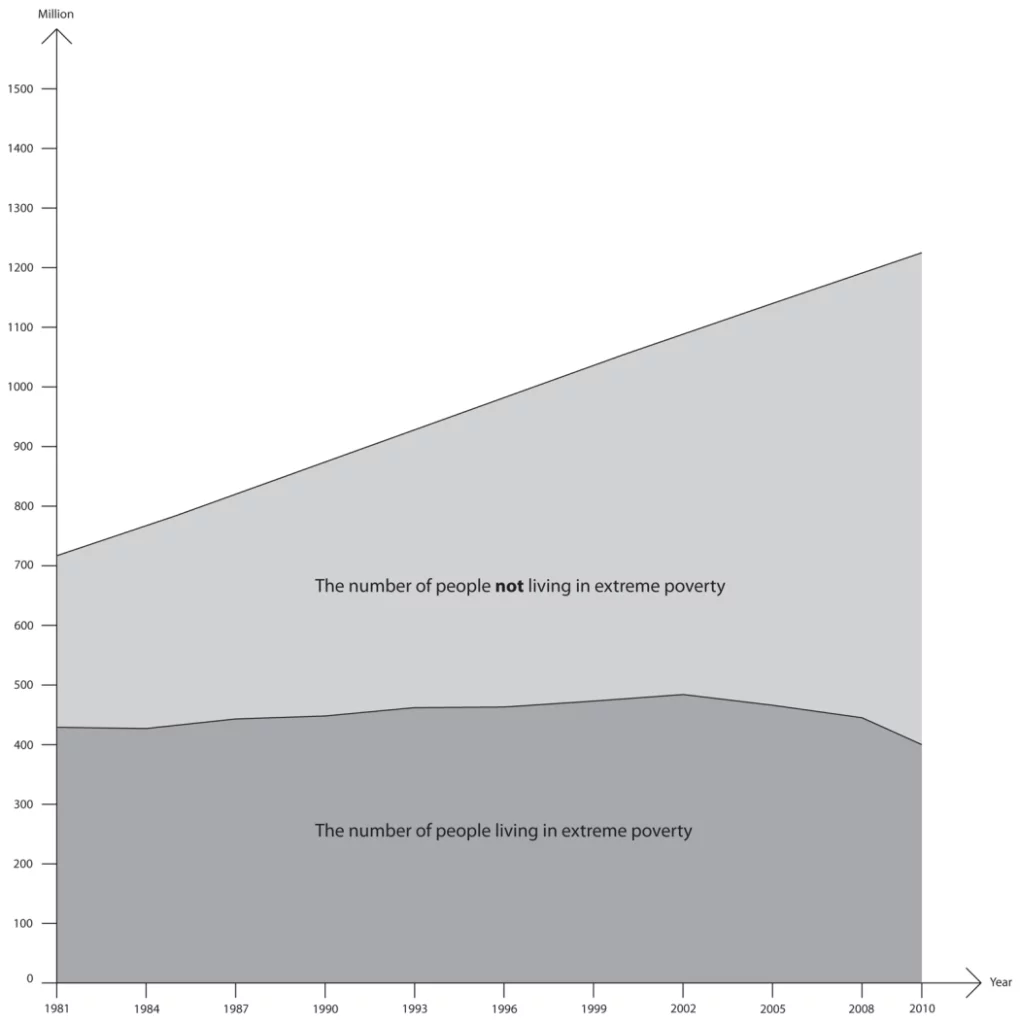

It can hardly be chalked up to the disparities between the two distinctly different political systems of China and India, as is often claimed, since both countries have the same systems today as they had thirty-five years ago, when there were twice as many extremely poor people in China as there were in India. Today, there are twice as many extremely poor in India as there are in China.21

However, one important political change did transpire in China some thirty-five years ago that hasn’t yet transpired in India. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Chinese leadership adopted a new strategy of development based on urbanization22 rather than on ruralization, which had been the strategy up until then not only in China but, to a great extent, in India, also. In India, however, there is still no clear consensus about which path to pursue. As a result, political initiatives are often mutually counterproductive.

Urban versus rural

An example of how deep the political ambivalence runs and how political initiatives are often mutually counterproductive, when it comes to rural versus urban development in India, is embodied by the enactment of two major national investment schemes in 2005, both of which were named after two of the greatest leaders of independent India. By providing poor rural households with at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment per year for unskilled manual work on infrastructural projects in rural areas, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act has helped lift millions of rural people just above the threshold of extreme poverty but it has concomitantly discouraged them from seeking better opportunities in cities. Meanwhile, the objective of The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, which was launched just three months later, was to improve urban infrastructures and provide basic services to the urban poor, something that might have helped integrate rural migrants in the cities, had they not just been encouraged to remain in the rural areas. By contrast, when China changed its development strategy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it not only provided incentives for urban growth but also implemented a series of reforms to make agriculture more efficient, thus effectively pushing millions of people into the new special economic zones and other urban areas, where low-skilled work in construction and manufacturing industries was awaiting their arrival. However, in the Indian cities, low-skilled workers often wind up in non-productive servant functions because many of the urban industries in India – such as its call centers, business process outsourcing and software industry – demand high-skilled labor.

And on the administrative level, in India, nothing much seems to be getting done when it comes to controlling or adapting to the rapid changes that Indian cities are currently undergoing.23

Urban life is thus becoming increasingly and unnecessarily hard for many people: with pollution and overexploitation making food and water scarce resources; with the exponential growth of motorized transportation causing accidents, pollution, stress and other lifestyle diseases, and environmental degradation; and with many people being pushed out to the peripheries of the cities, where opportunities are extremely limited.

But India also holds some keys that could – potentially – unlock its abundant resources and significantly improve the lives of its many people …

Inventiveness

One of these “keys” is the concept of jugaad, which roughly translates into inexpensive and creative inventions that are born out of necessity.

“Jugaad is practiced by almost all Indians in their daily lives to make the most of what they have. Jugaad applications include finding new uses for everyday objects […] or inventing new utilitarian tools using everyday objects.”24

An example of jugaad is the aforementioned mission to Mars, which was realized at only about 1/10 the cost of the nearly simultaneous launch of another mission to Mars by the United States.25

Another – perhaps more hands-on – example is the Hole-in-the-Wall experiment conducted by Sugata Mitra. He places a computer in a hole in the wall of an urban slum or under a tree in a remote village and lets the children figure out for themselves how to use the computer and how to educate themselves – learning new languages, for instance – through the Internet. He then connects the children to a group of British grandmothers (retired teachers), using cost-free Skype, who act as mentors for the children, and calls it “The School in the Cloud”.

Turning the concept of education upside-down, Sugata Mitra insists that education, in this day and age, ought to be about encouraging self-learning: “It’s not about making learning happen. It’s about letting it happen. The teacher sets the process in motion and then she stands back in awe and watches as learning happens.”26

And this can be done at a much lower cost than traditional education and, he believes, with much better results.

Self-organization

Another “key” is the concept of Swaraj.

Even though India has been ruled by both native and foreign dynasties, it also has a long history of decentralized control. Swaraj has to do with the self-rule of the individual or the self-governance of a community and has served as the inspiration for people’s movements, voluntary and non-governmental organizations. It stems from the ancient caste system and is, to some extent, used today in the local governance of villages, blocks and districts.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856 – 1920), whom the British called the “Father of the Indian unrest”, was one of the first and strongest advocates of Swaraj, saying that “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it!”27

Mahatma Gandhi, another strong advocate of Swaraj, believed that the system of centralized control alienated the people from the state and simultaneously enslaved them to it. He said that in a state based on Swaraj, “everyone is his own ruler. He rules himself in such a manner that he is never a hindrance to his neighbour.”28

The great minds of India

Yes, India is certainly facing some tremendous challenges. But why shouldn’t She get it right? After all, there is probably no other country that has fostered so many great social reformers – from Gautama Buddha (6th to 5th century B.C.) to Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948); so many great political thinkers – from Chanakya (370-283 B.C.), who conceptualized economics and political science, to Amartya Sen (1933 -), who was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to welfare economics; so many great scientists – from Aryabhata (476-550), who understood Earth’s rotation, to Satyendra Nath Bose (1894-1974), the father of the “God Particle”; so many great poets – from Valmiki, the author of the great epic, the Ramayana, to the Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) and the many anonymous people who contributed to India’s rich collection of folktales; and so many great rulers – from Ashoka of the Maurya Dynasty (304–232 B.C.) to Akbar the Great (1542-1605), who made India a multicultural and tolerant society. And probably no other country has fostered so much wisdom, including several major religions, yoga and meditation, the ancient science of medicine – the Ayurveda – and the ancient science of architecture – the Vastu Sastra, all of which seek to promote the natural balance and harmony of human beings and to promote balance and harmony between human beings and nature.

Notes

- Source: World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-urbanization-prospects-the-2011-revision.html (accessed 4 November 2017) ↩

- Asian countries that have been exposed to major famine after 1947 include China, where an estimated 20-40 million people succumbed to hunger during “The Great Leap Forward”; Bangladesh, where an estimated one million people perished during the famine of 1974; and North Korea, which has been exposed to repeated famine during recent decades. ↩

- Life expectancy in India has increased from 32 years in 1951 to 66 years today. Source: An Uncertain Glory – India and Its Contradictions; Jean Dréze and Amartya Sen; 2013 ↩

- Since the late 1960s, the production of wheat in India has increased more than eightfold: from 11,393,000 tons in 1967 to 94,880,000 tons in 2012. Source: FAOSTAT: http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx (accessed November 6, 2013). India has been self-sufficient with food since the early 1980s and is today a net exporter of food. Source: Rapid growth of selected Asian economies: Lessons and implications for agriculture and food security; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations; 2006 ↩

- Each and every year since 2001, more than 15,000 farmers have committed suicide in India. Source: Farmers’ suicide rates soar above the rest; The Hindu; May 18, 2013: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/sainath/farmers-suicide-rates-soar-above-the-rest/article4725101.ece ↩

- For a comparison of urban growth in China and India, see: Making India slum-free. ↩

- Quoted from: Impacts of Globalization on Social Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis to Gandhian Economic Philosophy; Dr. Pankaj Dodh; IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 5, May 2012. One reason for Gandhi’s focus on the rural aspects of Indian culture could be that the urban culture of India was, at that time, closely linked to the colonial power. In China, where foreign power was also concentrated in the cities, Mao Zedong adopted the same focus. Yet, in both countries, local resistance took shape and grew strong in urban rather than in rural areas. In China, discontent with foreign dominance and with the weak opposition of the Chinese emperor led to several uprisings, including the Boxer Rebellion in Beijing in 1900-01 and the riots in Wuchang (today Wuhan) in 1911, which eventually brought down the Qing Dynasty and ended more than two thousand years of imperial rule in China. The Communist Party of China was founded in Shanghai in 1921 and foreign influence in China came to a definitive end with the communist “Liberation” in 1949, which was, however, largely founded on peasant support obtained through the Long March across rural China from 1934-36.

In India, the first meeting of the Indian National Congress took place in Bombay (today Mumbai) in 1885. The leaders initially advocated cooperation with the British but after the unmotivated massacre of hundreds of non-violent protesters and pilgrims in the city of Amritsar in 1919 – known as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre – they began to favor non-cooperation and civil disobedience, emblematically manifested in Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March in 1930. The British Raj eventually came to an end in 1947 when India was given its independence.

It has been argued that globalization is a new form of colonization in which Western values are being spread across the rest of the world, especially in the form of new urban lifestyles. It must, however, be recalled that it was China and India that set globalization in motion – China by opening up the special economic zone of Shenzhen for foreign manufacturers and India by demarcating a large tract of land outside Bangalore for an electronic city – both in the late 1970s – and it must be recalled, also, that globalization has offered great opportunities to both China and India. ↩ - Two of the finest and most emblematic examples of how Indian culture has influenced and has been influenced by other cultures are two of the world’s greatest pieces of architecture – the Hindu Angkor Wat in Cambodia and the Islamic Taj Mahal in India. ↩

- “Seven and a half lakhs” equals seven hundred thousand. Quoted from: Impacts of Globalization on Social Inclusion: A Comparative Analysis to Gandhian Economic Philosophy; Dr. Pankaj Dodh; IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 5, May 2012. ↩

- Quoted from: Bricks and urbanism in the Indus Valley rise and decline; Aurangzeb Khan and Carsten Lemmen; 2013 ↩

- Source: A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century; Upinder Singh; 2008 ↩

- Source: The State of the Poor: Where are the Poor and where are they Poorest?; The World Bank; 2013 ↩

- Currently, 65 Indian individuals or families are worth more than a billion USD each. Source: India’s Richest; Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/india-billionaires/list/ (accessed March 3, 2014) ↩

- A recent survey across seven large states of northern India found that “half of the schools had no teaching activity at all”. Quoted from: An Uncertain Glory – India and Its Contradictions; Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen; 2013 ↩

- Only the Soviet Union/Russia, USA and Europe have made successful missions to Mars. Both Japan and China have failed. ↩

- It has been said that: “Whatever you can rightly say about India, the opposite is also true.” Joan Robinson, quoted in: The Argumentative Indian; Amartya Sen; 2005 ↩

- By “resources”, I mean to say both human resources, which are certainly abundant but remain largely unexploited, and natural resources, which would still be abundant if they were not polluted and overexploited. ↩

- The Environmental Performance Index; Yale University: http://epi.yale.edu/ (accessed March 10, 2014) ↩

- Source: India – Diagnostic assessment of select environmental challenges; The World Bank; 2013 ↩

- Quoted from: India: Green Growth – Overcoming Environment Challenges to Promote Development; Knowledge and News Network; March 6, 2014: http://www.knnindia.co.in/features/india:-green-growth–overcoming-environment-challenges-to-promote-development/26-5145.go ↩

- For a comparison of poverty in China and India, see: Making India slum-free. ↩

- The experiments with special economic zones in China since the late 1970s/early 1980s were essentially an experiment with urbanization as the driver of economic development because even though the city was not yet actually there, telling potential investors that there was going to be a vast pool of cheap labor and a dense network of infrastructures concentrated in one particular place was tantamount to saying that there would eventually be a city in that particular place. ↩

- This opinion is based on my own observations and on observations made by others that I have either read or with whom I have spoken. ↩

- Quoted from: Jugaad Innovation – Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Create Breakthrough Growth; Navi Radjou, Jaideep Prabhu and Simone Ahuja; 2012 ↩

- Source: From India, Proof That a Trip to Mars Doesn’t Have to Break the Bank; New York Times; February 17, 2014: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/18/business/international/from-india-proof-that-a-trip-to-mars-doesnt-have-to-break-the-bank.html?_r=2 ↩

- Quoted from: Build a School in the Cloud; Sugata Mitra; 2013: http://www.ted.com/talks/sugata_mitra_build_a_school_in_the_cloud ↩

- Source: Bal Gangadhar Tilak; Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bal_Gangadhar_Tilak (accessed February 17, 2014) ↩

- Quoted from: Swaraj; Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swaraj (accessed February 17, 2014) ↩