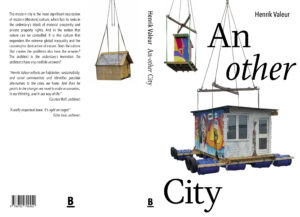

Debate book

Title: An-other City

Author: Henrik Valeur

Publisher: The Architectural Publisher B

Content: 264 pages

Publishing date: July, 2023

Language: English

ISBN: 978-87-92700-45-2

Comments

“Henrik Valeur reflects on habitation, sustainability, and social communities and identifies possible alternatives to the cities we know. And then he points to the changes we need to make in ourselves, in our thinking, and in our way of life”.

Carsten Hoff, architect

“A really important book. It’s right on target.”

Gitte Juul, architect

About

The modern city is the most significant expression of modern (Western) culture, which has its roots in the sedentary’s ideals of material prosperity and private property rights. And in the notion that nature can be controlled. It is this culture that engenders the extreme global inequality and the catastrophic destruction of nature. Does the culture that creates the problems also have the answers? The architect is the sedentary’s invention. Do architects have any credible answers?

Over the past decades, the development of cities in Denmark (and in most of the world) has been driven by developers and managed by technocrats. This development caters to some very specific population groups – those who are already affluent – and promotes an individualistic consumer culture. The author suggests a more anarchistic and experimental approach to urban development, which would give everybody direct influence on the design of their physical surroundings.

The book includes descriptions of the alternative urban development project, Musicon, in Roskilde, which was created without a master plan; an attempt to make an urban space on Badensgade, in Copenhagen, greener and more socially inclusive; and the struggle to save the outcasts’ self-created and self-organized settlement in Erdkehlgraven, also in Copenhagen. As an alternative to the current trend of developing the urban waterfronts, in total disregard of the prospect of rising sea levels, the book presents visions of floating communities and movable cities. The author seeks inspiration for other ways of contemplating and creating cities in the prehistoric Cucuteni-Trypillia culture and Freetown Christiania, in the works of Dostoevsky and Le Guin, in Daoist philosophy and wabi-sabi aesthetics, in theories of complementarity and complexity, and in Inuit culture and the Situationist movement.

An-other City is published on the occasion of the UIA World Congress of Architects in Copenhagen in 2023 and the city being named the World Capital of Architecture the same year. It is a combined, edited, and slightly rewritten English-language version of two small Danish debate books: En anden by (2021) and En anden by 2 (2023). The first book followed from a course on ‘En anden by’ (‘An-other City’) at the People’s University – an initiative for critical, creative reflection and action among activists and anarchists, dissidents and dreamers. The intention of the course was to strengthen the resistance against the developer-driven and technocratically managed urban development, and to develop alternatives to it, by exploring possibilities for a more spontaneous and self-organized form of urban development, based on the theory of development urbanism.

Table of Contents

A bit of a wild idea 8

Do you dare to believe in the revolution? 15

Whom do architects work for? 21

The building as an ironic comment 26

‘Leave no one behind’ 32

Welfare architecture? 44

Cities have become too neat 49

To the Prime Minister 55

The pirates’ and the pacifists’ common harbor 64

Nomads do not hoard, they share 82

Yes, Jørgen, it’s anarchy! 92

Can prehistoric experiments inspire future cities? 98

The city as a carnival 107

The architecture education must be reinvented 112

Less Aesthetics, More Ethics 120

Imagination is humankind’s most useful tool 133

A floating Freetown 139

The narrative of the green city is false 144

Experiments in car-freedom 150

This is why the car doesn’t belong in the city 158

Think of the city as nature 167

The Sustainable Development Goals do not improve cities 180

It starts with education 186

Think of time in architecture 193

Without a masterplan 198

The city does not end at the municipal boundary 204

A socially segregated and functionally divided region does not make a city 210

For what do we need Lynetteholm? 216

Can cities grow and shrink – at one and the same time? 220

The liquidation of the harbor 226

Move the city! 233

The Floating Community 246

A bit of a wild idea

It is said that the Communist Party of China, which is also the Chinese state, has made a contract with the Chinese people, which stipulates that as long as the party can deliver rising living standards and growing material consumption, it can remain in power. Isn’t this the same contract that the Welfare State of Denmark has made with the Danish people – that as long as a majority of the population can live an increasingly safe and comfortable life, and can live it for longer and longer, the current system can remain in power?

What is not immediately apparent from these contracts, or is written in print that’s so tiny that it’s not legible, are the potential costs. One of these is that we risk living a false and unfree life, steered by material needs, administrative requirements, and technological solutions – that we end up as the one-dimensional person (and society) that the sociologist Herbert Marcuse warned about over half a century ago, who passively and uncritically adapts to the prevailing norms.

Another potential cost is that the constantly growing material consumption, the pervasive administration, and the incessant technological development are destroying life on earth in a broader sense.

In just a few generations, poor agricultural and rural societies, where only the very few had too much and the vast majority had too little, have been replaced by modern, urban societies, where the vast majority have far more than they need.

Despite this, modern cities often resemble cheap department stores filled with standardized and mass-produced elements, created for a limited number of predetermined activities that are closely monitored and adjusted.

The uniform layout of our cities fits – and stimulates – a uniform behavior and mindset among people all over the world.

These cities are equipped with every conceivable convenience, and all practical problems are, as far as possible, already solved.

Everything is meticulously planned and laid out according to current rules and regulations. Nothing is left to chance, doubt, or uncertainty. There are no traces of an independent thought, a particular experience, or a unique idea. Any trace of lived life is removed, and as quickly as possible.

Since we have not been involved in creating these cities, we feel no connection to them. They have been created by technocrats and other so-called experts, developers and other so-called consultants, with the same limited life experience and the same unimaginative conception of the future.

In this spiritual wasteland, we flagellate ourselves and each other in order to be able to afford the material goods we are told will alleviate the feeling of emptiness and absence that characterizes modern urban life – seemingly without considering whether it is precisely this, the meaningless consumption, that gives rise to this feeling.

While we consume – and therefore pollute – more and more, and while our cities and the lives we live in them become more and more monotonous, politicians talk about the cities being sustainable and diverse. However, as soon as something stands out, or someone lives a bit differently, it is removed.

They talk about hearing and involving the citizens, but when those citizens cry out and demonstrate against the destruction of important historical cultural and natural environments, those in power still try to push through what has already been decided. And to enforce those decisions with force and violence.

New urban development projects are healthy, green, and livable, it is claimed, and a constant stream of exalted cheering, reviews and awards seems to confirm this. But at the same time, everyone can see that most of what is being built is of appallingly poor quality and without regard for either humans or nature.

Why are cities so dismissive of life – in its infinitely many and unpredictable forms?

Perhaps the explanation can be found in the classic Platonic-Christian contrast between life as an erratic mess and the metaphysical ideas as pure and eternal.(1) This dichotomy, which has shaped Western thinking for over two thousand years, is clearly expressed in the earliest modernist urban planners’ abstract visions for the city(2) – and in the later visions.

However, the explanation could also be somewhat more banal: that urban development is exclusively decided by people with power and money, or by people who act on their behalf. These people may feel that the more power they have, the more important they are. And that the more money they have, the better they are able to express their importance.

But that which makes sense in life, such as intimacy and affection, is not something that can be bought or decreed.

It is precisely in those parts of the city where people have defied, and refused to submit to, the tyranny of power and money, that social, cultural, and ecological consciousness is most evolved. This is where people have created their own milieus in which life sprouts in its own miraculous way.

It is not with more power and more money that one creates better conditions for life in cities, but with less power and less money. It’s not a matter of determining what cities should look like and how they should be used, but of creating opportunities for what we don’t know, what we don’t see, what we don’t understand … to unfold. The question is not how to afford more welfare and sustainability, as the politicians claim, but how to live better with less.

We should try to create the city together, instead of each of us buying (or renting) a small piece of it. Individually and as communities, we must try to reclaim the initiative and insist on our ‘right to the city’, which is a human right, as the urban theorist David Harvey says, a right that not only concerns access to the city’s resources, but is the right to change the city – and thus ourselves, the way we live our lives and interact with each other.

Even the Prime Minister, in her opening speech to the Danish parliament in 2020, said that some responsibility can indeed be entrusted to the people. Something she thought was “a bit of a wild idea,” but which she apparently found justification for in the fact that the population is quite well educated.

Perhaps this was just a politician talking, meaning that we may, instead, look forward to even more state paternalism as a consequence of the majority not being able to maintain the current level of material consumption in the long term. But it could also be that behind this statement, deeply hidden in the Prime Minister’s subconscious mind, is a recognition that the State cannot solve life’s big questions or make people satisfied with what they have. And that the answer to the great challenges humanity is facing cannot be found without the active involvement of each and every individual.

Perhaps it is these kinds of ‘wild’ ideas, such as giving people responsibility for forming, furnishing and maintaining their own surroundings, that can ensure positive conditions for life in the cities.

Because the other ideas haven’t been working.

1. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche claimed to be ”the first to see the intrinsic antithesis: here, the degenerating instinct which, with subterranean vindictiveness, turns against life (Christianity, the philosophy of Schopenhauer, in a certain sense already the philosophy of Plato, all idealistic systems as typical forms), and there, a formula of highest affirmation, born of fullness and overfullness, a yea-saying without reserve to suffering’s self, to guilt’s self, to all that is questionable and strange in existence itself.” Nietzsche, F. (1923 [1872]) The Birth of Tragedy. London, George Allen & Unwin, pp. 191-192 (Appendix, 1888).

2. See, for instance, the ‘father’ of modern urban planning, the engineer Ildefons Cerdà’s plan for the renewal and enlargement of Barcelona (1859) that became the new Eixample district. And his ‘General Theory of Urbanisation’ (1867), in which he writes: ”When I set out to observe the characteristics of human society and how it works when it is enclosed in large urban centers […] I found that it was concealed beneath a veil of mystery that had to be lifted. To understand and explain this organism, I was forced to engage in a profound analysis, a veritable anatomical dissection of each and every one of its constituent parts.” Cerdá, I. (2018 [1867]). General Theory of Urbanization 1867. Barcelona, Actar, pp. 53-54. In Cerdá’s theory, it is the technical, political, economic, legal and administrative aspects that decide the evolution of cities. See: Soria y Puig, A. (1999) Cerdá: the five bases of the general theory of urbanization. Madrid, Electa, pp. 36-37. Absent from his theory are the social and cultural aspects. And nature. Because even though he called the city an organism, “Cerdá nonetheless persisted in conceiving the problems of cities in purely geometrical, spatial terms.” He ”methodologically substituted for the living processes of urban realities the characteristics of a static object.” Fraser, B. ‘Ildefons Cerdà’s Scalpel: A Lefebvrian Perspective on Nineteenth-Century Urban Planning’. Catalan Review, 2011, XXV, pp. 185-186.