Introduction in Valeur, H. (2014) India: the Urban Transition – a Case Study of Development Urbanism. Copenhagen, The Architectural Publisher, pp. 10-26.

Based on Op-ed published in Information, 22 June 2010 (in Danish).

According to the United Nations, within the next thirty years, the world is going to be populated by around two billion more people, almost all of whom will be living in cities in the so-called “developing world”.

Population growth

The world’s total population is expected to rise from 6.9 billion in 2010 to 8.9 billion in 2040, while the urban population of the “less developed regions” is expected to rise from 2.6 billion in 2010 to 4.5 billion in 2040. In the “more developed regions”, the urban population is expected to increase by some 142 million people during the same period. Thus, the world’s entire future population growth is going to be absorbed by cities and 93 percent of the future urban growth will be taking place in the “less developed regions”, the prognosis also holds that rural areas are going to see a slight decrease in population.1

Building cities for such a large number of people within such a short span of time poses an enormous challenge and simultaneously presents an enormous opportunity. Depending on how it is done, it could either become one of humanity’s greatest successes or become one of our worst failures.

In many ways, population growth is problematic but it is better that it occurs in urban rather than in rural areas. One of the reasons for this is that we are better able to solve problems and make progress when we do it together, as we may do in cities. This is also why the evolution of cities and civilizations has always been closely intertwined.

Two billion new urban inhabitants could give an incredible boost to the development of our civilization!

Urban growth

In Europe and North America, it took about 200 years, from the beginning of the industrial revolution (in the middle of the 18th century) to add 400 million people to the urban population.2 Within the coming 20 years, more than three times as many people as this are expected to be added to the urban population in the “less developed regions”.3

Urban decline

Civilizations rise and prosper. However, at some point, it would seem, they start to decline. In order to survive, they may migrate, as did the Roman civilization when it shifted to Byzantium in the 4th century, or may reinvent themselves, as did the Chinese civilization when one dynasty replaced another; although both forms of transition often occurred with great human costs.

As civilizations decline, their greatest cities typically decay, as did Rome, or are completely erased, as was sometimes the case in China, when the imperial city of one dynasty was replaced by another.

One of the reasons for urban decline is … urban growth. As increased urbanization makes us more affluent, we tend to consume and to pollute more. The degradation and depletion of ecological resources may serve to bring a civilization down. But affluence, it would appear, also makes us more selfish. Moral decay and social disintegration resulting from a lack of mutual understanding, care and consideration may erode a civilization from within.4

A brief history of urbanization

It is no coincidence that the world’s first great civilizations arose in the fertile lands around the Tigris and the Euphrates, the Nile, the Indus River and the Yellow River. Here, agricultural production could feed large populations; this is a crucial precondition for the evolution of cities. In turn, the people who inhabited these cities could begin to think about other issues than that of providing food. This would lead to cultural, economic, political, scientific and technological advances that would shape those early civilizations.

Although they were located in different parts of the world, these civilizations did not develop in isolation. Throughout history, cities have been connected through trading routes that enabled the exchange of not only goods, but also of knowledge, thoughts and ideas. Probably the most important of these routes was the Silk Road, which connected Chang’an in the East with Rome in the West, meandering its way by land and by sea through a network of routes.

Western civilization reached a peak in ancient Rome, where new construction technologies and materials, including the concrete that was used for the construction of aqueducts, bridges, buildings and roads enabled the city to accommodate, already two thousand years ago, an estimated one million people. However, with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century followed a long period of de-urbanization in Europe, which is appropriately referred to as the “Dark Ages”, in which much of the ancient art, science and technology was either lost or transferred – via the eastern part of the empire5 – to the emerging Islamic world6 and from there, later on, back to Europe. (Concrete was re-invented in Europe in the 18th century!).

Chang’an, the present-day Xi’an, was the capital of several Chinese dynasties, including the Western Han (206 B.C. – 9 A.D.) and Tang (618 – 907 A.D.). In the days of the Western Han Dynasty, an imperial envoy, Zhang Qian, visited Persia and the Greek kingdoms to the east of Persia and described them as sophisticated urban civilizations, like the Han Dynasty itself. In order to open up commercial exchange with these civilizations, the Han rulers began developing the Silk Road by extending their rule to include “the 36 Walled City-States of the Western Regions”.

One of the important cities on the Silk Road was Taxila (in Sanskrit, “City of Cut Stone”), which was located in the Indo-Greek Kingdom at the intersection of three great routes conjoining it with the rest of India, Western Asia and Central Asia. Taxila was the home of one of the world’s earliest universities, which can be dated back as far as the 5th century B.C.

“When the men of Alexander the Great came to Taxila in India in the fourth century B.C. they found a university there the like of which had not been seen in Greece, a university which taught ‘the three Vedas and the eighteen accomplishments’ and was still existing when the Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hsien went there about A.D. 400.”7

It is believed that during the Tang dynasty, roughly two million people lived in the metropolitan area of Chang’an, half of them within the 30 square miles of the highly planned and organized city, behind a rectangular city wall. Back then, the citizens of Chang’an were reading printed books and following the passage of time on astronomical clocks, while enjoying the benefits of air conditioning, natural gas, sewage systems and … toilet paper.

Pyrrho (ca. 360 – 270 B.C.) was a Greek philosopher who travelled with Alexander the Great to the East, where he came into contact with the “naked wise men” of India, who are believed to have influenced his thinking, which later became the inspiration for the “school of Skepticism” in Western philosophy. He was quoted as saying that things are “undifferentiable, unmeasurable and indeterminable” and also that “for this reason, neither our sensations nor our opinions tell the truth or lie”.8

Faxian (earlier Fa-Hsien, ca. 337 – 422 A.D.) was a Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled along the Silk Road to India, where he visited the famous universities of Taxila and Nalanda, which were located, respectively, in present-day Pakistan and in the Indian state of Bihar and were connected to each other by the Grand Trunk Road. He brought back numerous Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit, which he translated into Chinese. Buddhism has had considerable influence on Chinese culture.

Al-Biruni (973-1048 A.D.) was a Persian scholar and polymath who travelled to India in 1017 and became “the most important interpreter of Indian science to the Islamic world”. In the introduction to his History of India (ca. 1030), he states that: “I shall place before the reader the theories of the Hindus exactly as they are, and I shall mention in connection with them similar theories of the Greeks in order to show the relationship existing between them”.9

Leibniz (1646-1716 A.D.) was a German mathematician and philosopher who is said to have founded modern rationalism (along with Descartes and Spinoza). He invented the binary numerical system, which is used in present-day computers, but attributed this invention to the yin-yang hexagrams found in the ancient Chinese Book of Changes (I Ching), although it obviously also owes a debt to the Indian invention of the number zero. His knowledge of other cultures was not based on travelling but rather on letters and on the reading that he did in libraries.

The concentration in cities of knowledge, thoughts and ideas – and the intellectual exchange between cities – has resulted in numerous inventions and innovations that have greatly improved human life. But cities also pose many dangers, like the infections that spread with deplorable sanitary conditions, like violence – in its many different forms – which breaks out for many different reasons, and like natural disasters, which may devastate entire cities.

Dangers may seem worse in urban areas than they do in rural areas, just as aircraft accidents may seem worse than car accidents, even though many more people die in car accidents. In fact, the city is often safer than the countryside because it is easier to provide assistance and protection to people who are concentrated in a small area rather than to people who are scattered over a large area.

However, the main reason for rapid urban growth in “developing” regions is not that cities are safer but rather that they often present the only hope of escaping rural poverty and despair.

The urban-rural dichotomy/unity

Although some of the greatest thinkers of all time, such as Buddha (Indian), Heraclitus (Greek) and Laozi (Chinese), advocated seclusion from society, they were all formed by the highly urbanized environments in which they grew up: Buddha as the crown prince Siddhartha Shakya of Kapilavastu, Heraclitus in an aristocratic family in the city of Ephesus, and Laozi, according to legend, was the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Zhou. Buddha left to meditate under the Bodhi tree, Heraclitus “wandered the mountains … making his diet of grass and herbs”10 and Laozi travelled to the westernmost gate of civilization – and beyond. They are believed to have lived during the same period – the 6th-5th century BC – which was an era dominated by city-states in China, in India and in Greece. Although they were geographically distanced from one another, they shared the same perception of reality as a dynamic whole that is undergoing continuous and cyclic changes, with opposites being mutually related and interdependent.

Lifting people out of poverty

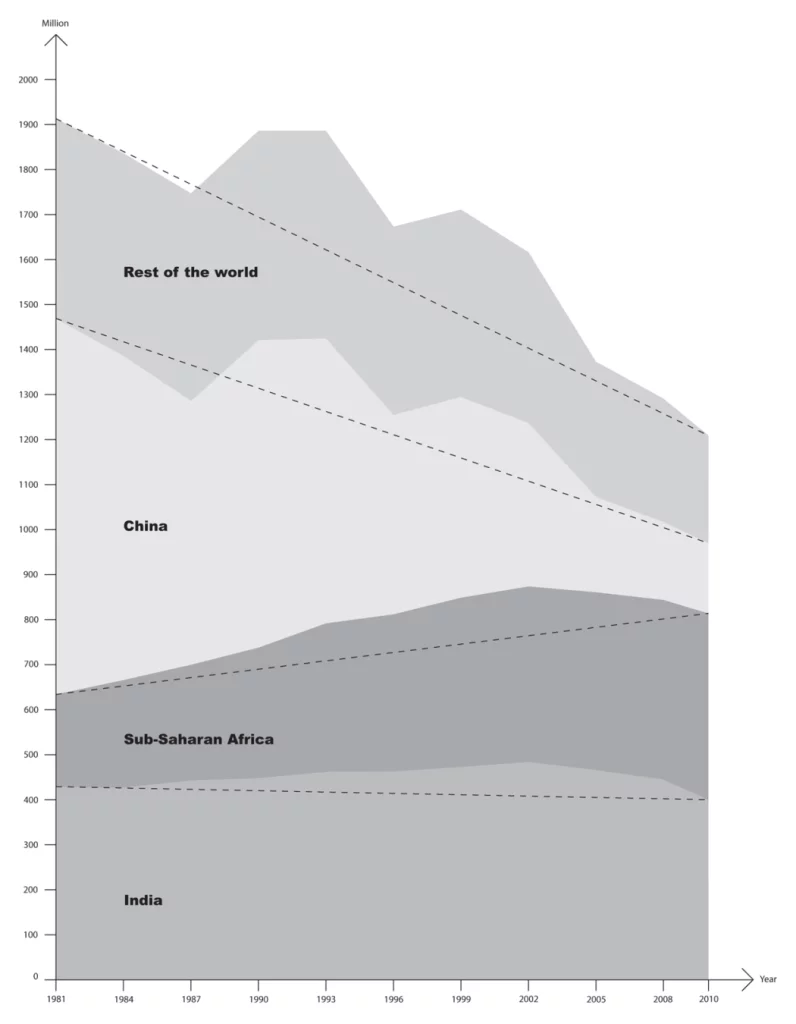

Today, 400 million children the world over are living in extreme poverty;11 many of them will probably never enter school12 and, although the relative rate of infant mortality has never been lower, millions of children still perish, each and every year, from pneumonia, malnutrition, diarrhea, malaria, infections and the like.

These problems are primarily rural problems. According to the World Bank, more than three quarters of the world’s poor live in rural areas.13 And for most of them, the only way to escape poverty is to move to cities, because agriculture and other rural activities will never be able to generate sufficient surplus to sustain the almost exponential population growth that “developing” countries are experiencing. Only cities can generate that kind of surplus.

Thus, instead of encouraging people to remain in the rural areas, as development aid generally does, people must be encouraged to move to cities, where living conditions, job opportunities, education and health care can and must be improved.

But this is going to require an enormous effort.

As it is, many of those who are moving to cities end up in slums, where living conditions are sometimes even more oppressive than what they were fleeing from in the countryside. Or they grow up in urban slums and are never able to leave the place and its oppressive conditions.

In recent decades, however, one country has successfully used urbanization as a means of fighting poverty. This country happens to be the one that has witnessed the most intense urban growth ever recorded on Earth.

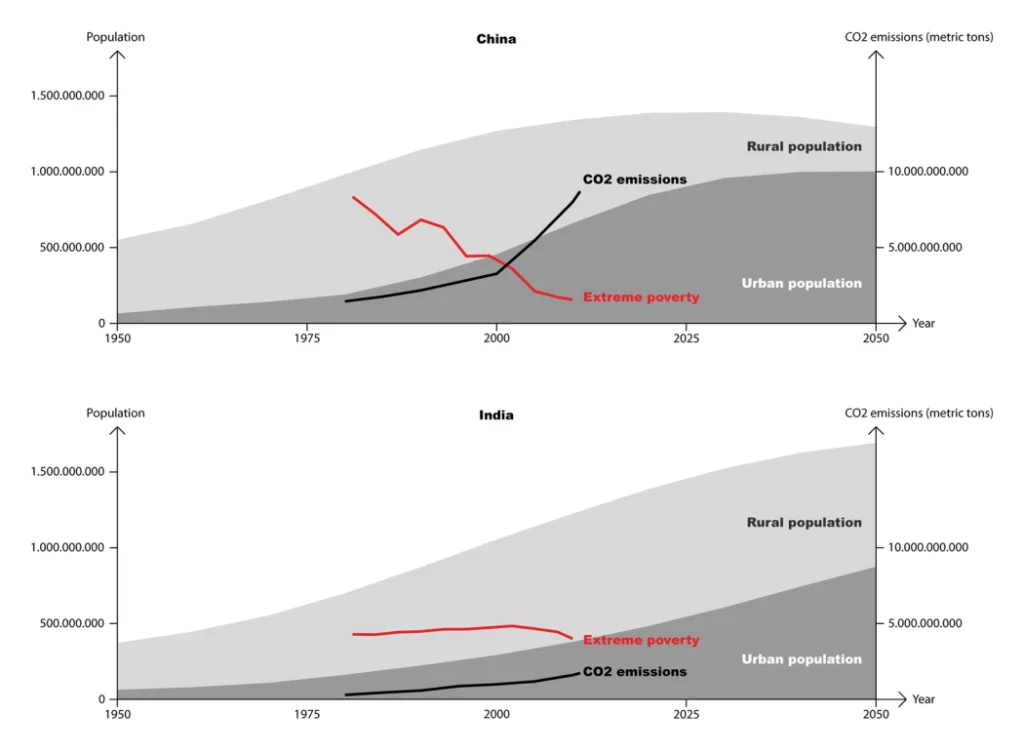

During the past three decades, the population of Chinese cities has increased by 15-20 million people, annually, while 20-25 million people have been lifted out of extreme poverty, annually.14

This is an incredible success story, from which we can learn a lot!

It all started in the early 1980s with the experiments of urbanization and market economy that Deng Xiaoping initiated in the coastal areas of Eastern China and with the agricultural reforms that enabled rural China to feed a growing urban population.

In 1980, 85 percent of the Chinese population lived in extreme poverty. Fewer than 20 percent of the people lived in cities. Thirty years later, in 2010, 49 percent of the Chinese population lived in cities and less than 12 percent of the people lived in extreme poverty.15

Despite the fact that the infant mortality rate in cities is significantly lower – and longevity significantly higher – than it is in rural areas, one of the consequences of urban migration is actually a reduction in the total population growth because people in cities simply have fewer children than their rural counterparts – even without the “one-child” policy which has been in force in China since the late 1970s.

China differs from other countries in many ways but the Chinese experience of lifting such a large portion of its population out of poverty could undoubtedly prove to be very valuable to other developing countries that are seeking to accomplish the same ends.

Some tremendous challenges still remain.

Environmental and social challenges

While most individuals move to cities in search of opportunities and the prospect of a better life, the potential common benefits of urbanization include cultural, economic and human development, scientific and technological progress, restricted land use16 and the stabilization of population growth. Even so, rather than solving the existing social problems that are related to exclusion and oppression and rather than solving the environmental problems that are related to pollution, resource depletion and ecological destruction, the current modes of urban development often serve to aggravate these problems.

As urbanization makes people wealthier, it also changes their patterns of consumption. Since it is the patterns of excessive consumption in the already urbanized regions that are causing the current environmental crisis, the rapid urban transition of the “less developed regions” could potentially turn this crisis into a full-blown catastrophe.

Still, many urban dwellers consume very little because even though they live – and make their living – in cities, they do not benefit from urbanization or they benefit only very modestly. They are – literally and/or figuratively – confined to the periphery of the city.

Extreme disparities

With the recent construction of what is supposedly the world’s most expensive home – the Antilia – one family has been provided with around 37,000 m2 of luxurious living space in the heart of Mumbai:17 a city that is arguably also the home of the world’s largest concentration of slums18 and where the average inhabitant has less than 5 m2 of living space available.19

Apart from the enormous common potentials that would be lost if two billion more people are to be kept on the periphery of the city this could also cause disruption of the social order, with unpredictable consequences for everyone.

The potential for social change

Following the shocking story of how a young female was gang-raped in Delhi, on December 16, 2012, and later succumbed to her injuries, thousands of people took to the streets of this city and other cities across South Asia to demonstrate for the rights and safety of women. Had the scene of this terrible crime been a rural village, nobody outside that village would probably ever have heard about the episode. In the city, however, the story struck the nerves of a wide audience of well-educated young people who are simply not willing to put up with the traditional forms of oppression in rural areas and the city enables them to join forces in their demand for change.

Co-Evolution

History bears out that urbanization can be used as a means of lifting people out of poverty. But can it also be a means for building up understanding, care and respect for other human beings and for nature?

The processes of urbanization are complex and dynamic. We should not pretend to be able to control them – or even to predict their outcome, which will be determined by an infinite number of individual circumstances, causes and motivations. But this does not mean that we should refrain from trying to push and influence the development in a certain direction.

Pushing the development in a more “sustainable” direction will require a more holistic and collaborative approach that would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of both the problems and the possibilities.

Cross-cultural and interdisciplinary collaboration, involving theoreticians and practitioners, activists and bureaucrats, individuals and communities, is regarded as the best way of addressing critical and complex common challenges that are related to the environment, resources and climate, social exclusion and oppression, human health and welfare.

Together, we may be able to find the solutions to these common problems. Individual solutions, that is to say, devised according to specific local conditions but integrating knowledge, thoughts and ideas from all around the globe.

As we become more and more interconnected and interdependent, human development is no longer a matter of the evolution of individual groups of people but rather a matter of the co-evolution of all people.

Development Urbanism

Development urbanism is a multidisciplinary field that is focused on sustainable urban development as a means of combating poverty and its related illnesses and of protecting the environment, the climate and the resources. It addresses basic human concerns in urban settings, seeing cities not as “dumb” machines but rather as sophisticated ecologies in which people are adapting to a constantly changing environment.

Urban development involves multiple interests and concerns and sustainable solutions have to integrate knowledge, thoughts and ideas from different cultures and from a diverse range of disciplines although these solutions must always be adapted to specific local conditions and must be developed in partnership with local stakeholders.

Development urbanism promotes novel methods of collaboration, which are based on an approach of “global collaboration related to local context”, in which international experts and specialists collaborate with local activists, bureaucrats, professionals and ordinary people on projects and programs that are related to specific urban conditions and situations, thereby establishing an ongoing learning and sharing process among a broad range of disciplines.

The aim is not only to reduce cities’ negative impact on the environment and to make cities more resilient to the consequences of that impact (i.e. extreme weather conditions, pollution and resource scarcity). The aim is also to make cities safer, healthier and more productive by integrating all of the citizens, including the poor, the disadvantaged and the outsiders, in the cultural, economic and political circuits of the city.

Notes

- Source: World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-urbanization-prospects-the-2011-revision.html (accessed 4 November 2017) ↩

- “The first urbanization wave took place in North America and Europe over two centuries, from 1750 to 1950: an increase from 10 to 52 per cent urban and from 15 to 423 million urbanites”. Quoted from: State of world population 2007 – Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth; UNFPA; 2007 ↩

- In the “less developed regions”, the urban population is expected to grow from 2.6 billion in 2010 to 3.9 billion in 2030. Source: World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-urbanization-prospects-the-2011-revision.html (accessed 4 November 2017) ↩

- For an insightful discussion of why civilizations fail, see: Immoderate Greatness – Why Civilizations Fail; William Ophuls; 2012 ↩

- The Eastern Roman Empire survived for another thousand years with the city of Byzantium, present-day Istanbul, as its capital. ↩

- Islam originated in the cities of Mecca and Medina in the 7th century A.D. At its zenith, the Islamic world stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to the Indian subcontinent. ↩

- Quoted from: Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West; Joseph Needham; 1969 ↩

- Quoted from: Pyrrho; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pyrrho/ (accessed January 1, 2014) ↩

- Quoted from: Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī; Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abū_Rayḥān_al-Bīrūnī (accessed January 2, 2014) ↩

- Quoted from: Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers; Diogenes Laërtius; 3rd century A.D. ↩

- Source: The State of the Poor: Where Are The Poor, Where Is Extreme Poverty Harder to End, and What Is the Current Profile of the World’s Poor?; The World Bank; 2013 ↩

- ”Of the 57 million out-of-school children of primary age, almost one-half (49%) will probably never enter school”. Quoted from: Schooling for millions of children jeopardised by reductions in aid; UNESCO; 2013 ↩

- 78 percent of the people living in extreme poverty live in rural areas. Source: The State of the Poor: Where Are The Poor, Where Is Extreme Poverty Harder to End, and What Is the Current Profile of the World’s Poor?; The World Bank; 2013 ↩

- The reason why the number of people who were lifted out of poverty is higher than the number of people who moved to cities can be explained by the fact that not only are the ones who move to cities able to escape poverty themselves: they are also often able to send money back to their relatives in rural areas, thus helping them escape poverty, too. ↩

- In 1980/81, out of a total population of 983 million, 835 million people lived in extreme poverty in China. At that time, there were 190 million people living in cities in China. In 2010, out of a total population of 1,341 million, 660 million people lived in cities and 156 million people lived in extreme poverty. Sources: World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-urbanization-prospects-the-2011-revision.html (accessed 4 November 2017) and The State of the Poor: Where Are The Poor and where are they poorest?; The World Bank; 2013 ↩

- In principle, people living close together in cities take up less land than people living in rural (or suburban) areas. Thus, in principle, more land can be preserved for nature. In reality, however, urban dwellers usually consume more products and products which require cultivation or mining of more land, than rural dwellers. ↩

- Source: Antilia (building); Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antilia_(building) (accessed January 30, 2014) ↩

- An estimated 7.2 million people, or 58% of Mumbai’s total population, live in slums, occupying only 37 km2, or barely 6 percent of the total urban area. Source: Slumdwellers 72.5 lakh, live on 6.13% Mumbai land; Indian Express p.3; July 26, 2012: http://realestateclips-realestateclips.blogspot.dk/2012/07/slumdwellers-725-lakh-live-on-613.html(accessed 4 November 2017) ↩

- “With an estimated average of about 4.5 m2 per person in 2009, the consumption of residential floor space in Mumbai is one of the lowest in the world”. Quoted from: Mumbai FAR/FSI conundrum; Alain Bertaud; 2011 ↩